17 October 1817

Delhi, Mughal Empire

Died

27 March 1898 (aged 80)

Aligarh, North-Western Provinces, British India

Other names

Sir Syed

Notable work

The Mohammadan Commentary on the Holy Quran (tafsir on Quran).

Children

Syed Mahmood

Relatives

Ross Masood (grandson)

Awards

Star of India

Era

19th-century

School

Islamic and Renaissance philosophy

Institutions

East India Company

Indian Judicial Branch

Aligarh Muslim University

Punjab University

Government College University

Main interests

Pragmatism, metaphysics, language, aesthetics, Christianity and Islam

Notable ideas

Two-nation theory, Muslim adoption of modernist ideas

In nineteenth-century British India, Sir Syed Ahmad Khan KCSI, FRAS (17 October 1817

– 27 March 1898), also spelled Sayyid Ahmad Khan, was a Muslim reformer, philosopher, and educator .

He was the forerunner of Muslim nationalism in India and is largely recognized as the founder of the two-nation idea, which served as the foundation for the Pakistan movement, despite his earlier support for Hindu-Muslim unity. Ahmad, who was born into a family with close ties to the Mughal court, studied the Quran and science there. In 1889, the University of Edinburgh granted him an honorary LLD.

Syed Ahmad began working for the East India Company in 1838. He later rose to the rank of judge at a Small Causes Court in 1867 and retired in 1876. He was faithful to the British Raj throughout the Indian Mutiny of 1857 and was renowned for his efforts to save European lives.He wrote the booklet The Causes of the Indian Mutiny after the uprising, which at the time was a bold indictment of several British policies that he held responsible for the uprising. Sensing that the inflexibility of the Muslim worldview threatened their future, Sir Ahmad started advocating for Western-style scientific education by establishing contemporarypublications, schools, and arranging Islamic business owners. A scientific society for Muslims in 1864, and Victoria School in Ghazipur in 1863. established the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College, Southern Asia’s first Muslim university, in 1875. Syed pushed for Urdu to become the common language of all Indian Muslims and frequently urged Muslims to serve the British Raj with loyalty during his career. The Indian National Congress came under fire from Syed.

Both among Indian Muslims and in Pakistan, Sir Syed has left a lasting legacy. Muhammad Ali Jinnah and Allama Iqbal were among the activists of the Pakistan Movement who found inspiration in him. His championing of Islam’s rationalist legacy, and a broader, radical reconstruction of the Quran to make it compatible with science and modernity, continues to impact the global Islamic reformation.In Pakistan, Sir Syed is the name of numerous public structures and universities.On October 17, 2017, Aligarh Muslim University enthusiastically commemorated the 200th anniversary of Sir Syed’s birth.

Early life

In Delhi, the capital of the Mughal Empire under Akbar II, Syed Ahmad Taqvi ‘Khan Bahadur’ was born on October 17, 1817, to Syed Muhammad Muttaqi and Aziz-un-Nisa. His family had ties to the Mughal government that spanned several generations. In the court of Emperor Akbar Shah II, his maternal grandfather, Khwaja Fariduddin, held the position of Wazir. Syed Hadi Jawwad bin Imaduddin, his paternal grandpa, served in Emperor Alamgir II’s court as “Mir Jawwad Ali Khan” and held a mansab (lit. General), a high-ranking administrative position. Emperor Akbar Shah II was particularly close to Sir Syed’s father, Syed Muhammad Muttaqi, who also advised him personally.Syed Ahmad, however, was born during a period when his father was active in local uprisings supported and directed by the East India Company, which had supplanted the Mughal state’s former authority and reduced its ruler to a symbolic figure.

The youngest of three siblings was Syed Ahmad. In a posh part of the city, Sir Syed grew up in his maternal grandfather’s home with his older brother Syed Muhammad bin Muttaqi Khan and older sister Safiyatun Nisa . They were introduced to politics and brought up strictly in line with the lofty traditions of the Mughals. Aziz-un-Nisa, their mother, was a significant influence on Sir Syed’s early years, instilling in him a strong emphasis on modern education and strict discipline.

Notable ideas

Notable members

Notable institutes

Publications

Associated Movements

Education

His father’s spiritual guide, Shah Ghulam Ali, began Sir Syed’s schooling in 1822. A female tutor named Areeba Sehar taught him how to read and comprehend the Qur’an.He was educated in Delhi in a manner typical of Muslim aristocracy. Muslim writers and scholars including Sahbai, Zauq, and Ghalib were among those he read. He received instruction in algebra, astronomy, and mathematics from other tutors. He also spent a number of years studying medicine under Hakim Ghulam Haider Khan.In addition, Sir Syed was skilled at shooting, swimming, and other sports. He actively participated in the cultural events of the Mughal court, going to recitations, festivals, and celebrations.

One of the first Urdu publications in northern India was “Syedul Akhbar,” a weekly published from Delhi by Syed Ahmad’s older brother. Sir Syed had led a life typical of a prosperous young Muslim aristocrat until his father’s death in 1838. He inherited his father’s and grandfather’s titles after his father passed away, and the emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar bestowed upon him the title of Arif Jung. Sir Syed’s formal schooling ended due to financial constraints, although he continued to study in private utilizing books on a range of topics.

Career

Sir Syed made the decision to join the East India Company after observing the gradual erosion of Mughal political influence. Only in the 1860s were Indians allowed to join the colonial civil service, hence he was unable to do so. At the Sadr Amin’s office in Delhi, he was initially assigned as a Serestadar (lit. Clerk) of the Criminal Department, where he was in charge of maintaining court records and overseeing court operations. In February 1839, he was moved to Agra and elevated to the position of Naib Munshi, or deputy reader, in the Commissioner’s office.After serving as the Munsif or Sub-Judge of Fatehpur Sikri in 1841, he was moved to Delhi in 1846.Except for two brief assignments to Rohtak in 1850 and 1853 as an officiant of Sadr Amin, he stayed in Delhi till 1854.He received a promotion to Sadr Amin in Bijnor in 1855.

Syed Mahmood, he was the first Muslim to serve as

a High Court judge in the British Raj.

During his time at the courts, Sir Syed gained intimate knowledge of British colonial affairs and became acquainted with high-ranking British officials. Sir Syed was the principal assessment officer of the court in Bijnor on May 10, 1857, when the Indian insurrection broke out. He supported the British officers in Bijnor and prevented the rebellious soldiers from killing numerous officers and their families. Numerous civilians had been killed in the war. Former Muslim strongholds like Delhi, Agra, Lucknow, and Kanpur suffered greatly. The violence claimed the lives of numerous of his close relatives. Despite his success in saving his mother from the chaos, she passed away in Meerut as a result of the hardships she had endured.

He started writing his best-known book, The Cause of the Indian Revolt, in 1858 after being appointed as Sadarus Sudoor, a high-ranking position at the court in Muradabad. He was moved to Aligarh in 1864 after first being moved to Ghazipur in 1862. He was transferred to Banaras in 1864 and made a Sub-Judge of Small Causes.

He traveled to England with his two sons, Syed Hamid and Syed Mahmood, in April 1869. The latter having secured a scholarship to study in England.

In 1876, Sir Syed left the ministry and moved to Aligarh.He served from July 1878 to July 1880 after being nominated as an additional member of the Imperial Legislative Council in 1878. In addition, he held office until 1883 for a second term.From 1887 until 1893, he held two terms as a member of the Legislative Council of the Lieutenant Governor of the North-Western Provinces.

Influences

Early on, Sir Syed was influenced by his maternal grandpa Khwaja Fariduddin and mother Aziz-un-Nisa, who both showed a keen interest in his education. Khwaja Fariduddin was a teacher, mathematician, and astronomer in addition to being a Wazir in the Mughal court. Additionally, he had a tendency toward Sufism, which affected Sir Syed from a young age. He was also influenced in his early years by his maternal uncle, Khwaja Zainuddin Ahmad, who was a master of mathematics and music.

Three schools of religious thought influenced Sir Syed’s outlook, as evidenced by his early theological writings: the Mujahidin movement of Syed Ahmad Barelvi and his first disciple Shah Ismail Dehlvi; the Naqshbandi tradition of Shah Ghulam Ali Dahlavi; and Shah Waliullah Dehlawi and his teachings.Sir Syed rejected the Indian Wahhabi movement, even though he supported the Mujahidin movement’s objective for religious forms in India.

His early years in Delhi were spent interacting with Ghalib and Zauq, whose beautiful prose and poetry impacted Sir Syed’s writing. During his formative years, he frequently visited Sadruddin Khan Azurda Dehlawi and Imam Baksh Sahbai.His companion and teacher in Agra, Nur al Hasan of Kandhala, who taught Arabic at Agra College in the early 1840s and supported and edited his early writings, had another impact on him.

He also took inspiration from the writings of Hayreddin Pasha, a Tunisian reformer, and embraced his strategy of using the right to free speech to advance reforms within the Muslim community.

He frequently cited utilitarian scholars like John Stuart Mill in his own writings, who were the western authors that had the biggest impact on his political ideas.The writings of Richard Steele and Joseph Addison also had an impact on him, and he based his personal diaries on their Tatler and Spectator.

Works of literature

While still working as a junior clerk, Sir Syed started writing at the age of 23 (in 1840) on a variety of topics, primarily in Urdu, covering topics ranging from mechanics to educational difficulties. He authored at least 6000 pages in this time. In addition, he authored the well-known archeology book Athar-ul-Sandeed. After meeting some of India’s most renowned authors, he also became interested in literature.

Works of religion

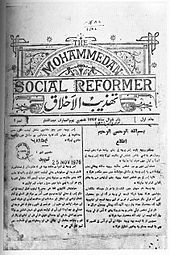

a groundbreaking periodical

started by Sir Syed to advance

liberal ideas in Muslim society,

published its first issue

on December 24, 1870.

In 1842, Sir Syed Ahmad Khan wrote a number of treatises on religious topics in Urdu, which marked the beginning of his writing career. His theological ideas were more conventional in his early writings; nevertheless, as his exposure to the West grew, his opinions progressively shifted toward independence.His early writings demonstrate the impact of his Delhi upbringing and Sufism. The desire to reform Indian Muslims’ lives from religious innovations and to promote the traditions of the Islamic prophet Muhammad as the only authentic route are the primary themes of these works, which aim to preserve the purity of Islamic belief in India.

Christian missionary work in India and British historians’ hostile attitude toward Islam served as catalysts for his later religious writings, including his articles on Muhammad and his commentary on the Torah and Gospel.

The first treatises

In keeping with Shah Waliullah’s reformist beliefs, his first work, Jila al-Qulub bi Zikr al-Mahbub (Delight of the Hearts in Remembering the Beloved), was a biographical sketch of Muhammad that was published in 1842 . It was idiomatic Urdu literature intended for recitation on Mawlid.Encouraged by his companion Nur al Hasan, he released his second treatise, Tuhfa-i Hasan (The Gift to Hasan), in 1844. The 10th and 12th chapters of Shah Abdul Aziz Dehlavi’s Tuhfah-i Ithna Ashariyya (A treatise on the 12 Imams), which was a critique of Shia doctrines, are translated into Urdu.The Shia allegations against the Sahabi and Hazrat Aisha are addressed in the tenth chapter, while the Shia concepts of Tawalli are covered in the twelfth.

In 1849, he released his third book, Kalimat al-Haqq (The True Discourse). It is a criticism of the common Sufi customs surrounding pir-murid partnerships. The idea of piri is the focus of the first section of the piece. He makes the case that Muhammad is the one legitimate pir in this section. Muridi and the concept of bay’ah are the main topics of the second section of the text. He demands changes to the pir-murid connection and related customs. His fourth treatise, Rah i Sunna dar radd i Bid’a (The Sunna and the Rejection of Innovations), was released in 1850. He voiced his disapproval of some of his fellow Muslims’ religious customs and beliefs in this work because he believed they were infused with modernity and departed from the realHe advocated tasawwur-i-Shaikh, the Sufi practice of seeing the image of one’s spiritual guide within, in his 1852 book Namiqa dar bayan masala tasawwur-i-Shaikh (A Letter Explaining the Teaching of tasawwur i shaikh). He translated a few sections of Kimiya al Sa’ada (The Alchemy of Happiness), written by al-Ghazali, in 1853.

Analysis of the Gospel and Torah

While stationed in Ghazipur in 1862, Sir Syed began writing a commentary on the Bible and its teachings with the intention of elucidating them in terms of Islam. Tabin al-al-kalam Fi tafsir altawrat Wa ‘I-injil’ala millat al Islam (Elucidation of the World in Commentary of the Torah and Gospel According to the Religion of Islam) was the title published between 1862 and 1865 in Urdu and English. The first section discusses the Islamic perspective on biblical texts, while the second and third sections offer commentary on the Book of Genesis and the Gospel of Matthew, respectively.

Essays on Muhammad’s Life

He responded to William Muir’s well-known four-part work, The Life of Mahomet, published in 1864 with Al-Khutbat al-Ahmadiya fi’l Arab wa’I Sirat al-Muhammadiya (A Series of Essays on the Life of Prophet Muhammad and Subjects Subsidiary Therein) in 1869. Muir’s depiction of Islam and Muhammad’s personality severely troubled him. He was worried that the book might cause Muslims in the younger generation to have second thoughts. He traveled to England with his son to obtain a firsthand look at Western civilization in order to prepare for the book.

Syed Ahmad was among the first in the Islamic world to embrace this viewpoint; he read Darwin and, although he did not agree with all of his ideas, he could be described as a theistic evolutionist like his contemporary Asa Gray. He supported the idea with quotes from earlier Islamic scholars such as Al-Jahiz, Ibn Khaldun, and Shah Waliullah, as well as with results from his own scientific research

Tafsir-ul-Quran

In 1877, Sir Syed began writing a tafsir, or commentary on the Quran. Tafsir ul-Quran was published in seven volumes, the first of which came out in 1880 and the last of which came out in 1904, six years after his passing.He examined and interpreted 13 surahs and 16 paragraphs of the Quran in this book.[80] He also provided a thorough article in the first volume called Tahrir fi Usool al-Tafsir (The Notes on the Principles of interpretation), in which he outlined 15 principles that served as the foundation for his interpretation.

Works of history

Sir Syed’s favorite subject was history, and in 1840, at the request of his patron Robert N. C. Hamilton, he wrote a book with chronological tables about the Timurid kings of Delhi from Timur to Bahadur Shah Zafar. Later, it was released with the title Jam-i-Jum, which translates to “Jamshed’s Cup.”He collected the biographies of all Delhi’s past kings in Silsilat-ul-Mulk.He authored a history of Bijnor when he was there, but it was destroyed in the uprising in 1857. In addition, he authored critical editions of works such as Tuzk-e-Jahangiri (1864) and Tarikh-e-Firoz Shahi (1862) by Ziauddin Barani.However, the two editions of Asar-us-Sanadid and Ain-e-Akbari were his most significant historical writings and the ones that made him a renowned scholar.

Asar-us-Sanadid

He documented Delhi’s medieval antiquities in his book Asar-us-Sanadid (The Remnants of Ancient Heroes), which was released in 1847. In the first section, the buildings outside the city of Delhi are described; in the second, the buildings surrounding the Delhi Fort are described; in the third, the monuments in Shahjahanabad are described; and in the final section, a brief historical account of Delhi’s various settlements and notable residents, including Sufis (like Shah Ghulam Ali and Saiyid Ahmad Shahid), doctors, scholars, poets, calligraphers, and musicians, is given It also had over 130 pictures, the first lithographically made book illustrations in India, created by Faiz Ali Khan and Mirza Shahrukh Beg.In 1854, Syed Ahmad published Ansar-as-Sanadid in its second edition. But the second version was drastically different from the first; it was more factual and condensed. Sir Syed gained greater recognition and a reputation as a learned scholar as a result of this work.Gracin de Tassy translated it into French in Paris in 1861. He was also made an honorary fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland in London when the book was handed to them.

Ain-e-Akbari

a picture from a

manuscript of

the Ain-e-Akbari

He completed his academic, illustrated version of A’in-e Akbari by Abul Fazl in 1855. The work’s first and third volumes were both released in 1855. When the insurrection occurred in 1857, the second book, which had been sent to the publisher, was destroyed. Syed Ahmad approached the great Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib to write a taqriz (a laudatory foreword in the days’ convention) for the work after completing it to his satisfaction and thinking that Ghalib would value his efforts. Although Ghalib complied, he produced a brief Persian poem that was critical of the A’in-e Akbari and, implicitly, the imperial, opulent, literate, and intellectual Mughal culture from which it originated.The book’s low worth, even as an antique document, was the least that could be said against it. Syed Ahmad Khan was essentially chastised by Ghalib for squandering his skills and time on pointless endeavors. Even worse, he extolled the “sahibs of England” who, at the time, had all the secrets to the world’s a’ins.

Sir Syed Ahmad Khan actually stopped being actively interested in history and archeology and never again wrote anything praising the A’in-e Akbari. Over the following few years, he edited two more historical works, but they were not quite as extensive and triumphalist as the A’in, which details Akbar’s rule.

Works of politics

Sir Syed served as the principal evaluation officer at the court in Bijnor during the 1857 rebellion. In Tarikh i Sarkashi-ye Bijnor (History of the Bijnor Rebellion), published in 1858, he documented the mutiny’s history.[98] He was particularly concerned about how the revolt would affect his fellow Muslims. He produced several pamphlets and essays, including Review of Dr. Hunter’s Indian Musalmans: Are They Bound in Conscience to Rebel Against the Queen, Loyal Muhammadans of India, and Asbab-e-Baghawat-e-Hind (The Causes of the Indian Revolt). to establish friendly relationships between the Muslim community and the British government while defending Muslims and Islam.

The Indian Revolt’s causes

Jamaluddin Afghani and other nationalists have criticized Sir Syed’s support for the East India Company during the 1857 rebellion. The causes of the Indian uprising were examined by Sir Syed, who released the booklet Asbab-e-Baghawat-e-Hind (The Causes of the Indian uprising) in Urdu in 1859. In his most well-known work, he disproved the widely held belief that Muslim elites, who were angry at the declining power of Muslim monarchs, were behind the plot. He attributed the rapid expansion to the East India Company and British policymakers’ lack of knowledge about Indian culture. Sir Syed suggested that the British assign Muslims to help with administration in order to stop what he referred to as “haramzadgi,” or a disgusting act, like mutiny.

Maulana Altaf Hussain Hali stated in Sir Syed’s biography:

“Sir Syed started writing The Causes of the Indian Revolt (Asbab-e-Baghawat-e-Hind) as soon as he arrived in Muradabad. In it, he tried his utmost to absolve the Indian populace—Muslims in particular—of the charge of mutiny. He bravely and thoroughly reported on the charges being made against the government despite the clear danger, rejecting the British-developed thesis that attempted to explain the reasons behind the mutiny.

Upon completion, Sir Syed forwarded the Urdu version to be printed at the Mufassilat Gazette Press in Agra without waiting for an English translation. The printers returned 500 copies to him in a matter of weeks. He was cautioned by one of his friends not to transmit the leaflet to the Indian government or the British Parliament. Sir Syed’s close friend Rae Shankar Das pleaded with him to burn the books instead of risking his life.[98] For the benefit of his own people, his nation, and the government itself, Sir Syed retorted that he was bringing these issues to the British government’s notice.

He declared that he would cheerfully endure whatever happened to him if he were hurt while carrying out an action that would directly benefit India’s rulers and subjects. When Rae Shankar Das realized that Sir Syed had already made up his mind and that there was nothing he could do to alter it, he sobbed and said nothing. Following an additional prayer and a request for God’s favor, Sir Syed shipped nearly all of the 500 copies of his pamphlet to England, gave one to the government, and kept the other ones for himself.

Both Sir Bartle Frere and Lord Canning, the governor-general, recognized the book as a genuine and cordial report when the Indian administration had it translated and brought it to the council.Cecil Beadon, the foreign secretary, harshly condemned it, referring to it as ‘an very seditious tract’. He called for a thorough investigation into the issue and stated that the author should face severe consequences unless he could provide a convincing explanation. His attack was ineffective since no other Council member shared his viewpoint.[102]

Later, Sir Syed saw the foreign secretary in Farrukhabad when he accepted an invitation to Lord Canning’s durbar. He expressed his displeasure with the pamphlet to Sir Syed and stated that if he had truly cared about the government’s interests, he would not have spread his views across the nation in this manner but would have spoken with the administration directly.

In response, Sir Syed stated that he had printed just 500 copies, most of which he had shipped to England, one of which he had handed to the Indian government, and the rest of which he still retained. And he could verify it with the receipt. He added that he was conscious of how the stress and anxiety of the times had warped the rulers’ viewpoint, making it hard to see even the most basic issue in the proper light. He had not spoken his opinions in public because of this. He pledged to personally pay 1,000 rupees for each copy that was discovered to be in circulation in India.Unconvinced at first, Beadon repeatedly questioned Sir Syed about his assurance that no further copies had been distributed in India. He was reassured by Sir Syed on this point, and Beadon never brought it up again. He then turned into one of Sir Syed’s most ardent admirers.

The Causes of the Indian Revolt’s Urdu text has been translated numerous times by official translations. The one carried out by the India Office was the focus of numerous conversations and arguments. The Indian government and a number of parliamentarians also translated the leaflet, but the public was not given access to a translation. A government official named Auckland Colvin began the translation, which Sir Syed’s friend Colonel G.F.I. Graham completed.

Devoted Muslims in India

Sir Syed wrote a series of bilingual pamphlets from Meerut in 1860 called the Risala Khair Khwahan-e Musalmanan-e-Hind (An Account of the Loyal Mohammedans of India) that included stories about the lives of Muslims who supported the British during the 1857 uprising. The book was published in three issues, the first and second of which came out in 1860 and the third in 1861. The first issue focused on the bravery of the Muslims who supported the British, while the second issue featured an article on jihad in which he clearly distinguished between jihad and rebellion.

An analysis of Indian Musalmans in Hunter

In his book Indian Musalmans: Are They Bound in Conscience to Rebel Against the Queen? published in August 1871, Scottish historian William Wilson Hunter discussed the Indian Wahabi movement, its role in the rebellion, and his argument that Muslims were a threat to the Empire. Hunter associates Wahhabism with rebellion and calls them self-stylized jihadis. As a result of his accusations, Muslims in India, particularly in the North Western Provinces, were prosecuted, and those linked to Wahhabism suffered harsh punishment. Many Muslims felt that Hunter’s arguments were biased, which prompted Sir Syed to write a response to the book.

Reformer of Islam

Syed Ahmad Khan started to become very passionate about education in the 1850s. Sir Syed became aware of the benefits of Western-style education, which was being provided at recently founded colleges throughout India, while studying a variety of disciplines, including European jurisprudence. Even though Sir Syed was a devoted Muslim, he criticized the impact of religious conservatism and conventional doctrine, which had caused the majority of Indian Muslims to be wary of British influences. Sir Syed started to worry more and more about what would happen to Muslim communities.Sir Syed, a descendant of Mughal aristocracy, had grown up in the best traditions of Muslim elite culture and was conscious of the gradual erosion of Muslim political power in India, where the British-Muslim hostility prior to and following the Indian Rebellion of 1857 threatened to marginalize Muslim communities for many generations .

The Scientific Society

In order to encourage cooperation with British authorities and to foster devotion to the Empire among Indian Muslims, Sir Syed stepped up his efforts. In 1859, Sir Syed established a contemporary madrassa in Muradabad, which was among the first Islamic institutions to offer scientific instruction, as part of his dedication to advancing the cause of Muslims. In 1860, Sir Syed assisted in planning relief efforts for the famine-stricken residents of North-West Province as part of his work on social concerns.In 1863, while sent to Ghazipur, he founded a madrasa that subsequently evolved into the Victoria High School. In Ghazipur, he also founded the Scientific Society to advance national educational reforms.

After being transferred to Aligarh in 1864, Sir Syed devoted himself fully to his work as a teacher. The Scientific Society was renamed the Scientific Society of Aligarh after being moved from Ghazipur to Aligarh. In an attempt to model it after the Royal Society and the Royal Asiatic Society, Sir Syed brought together Muslim experts from all over the nation. The Society published a journal on scientific topics in Urdu and English on a regular basis, hosted yearly conferences, and gave money for educational reasons. Sir Syed believed that the conventional dislike of contemporary science and technology by Muslims was a threat to their socio-economic future.

He struggled to come up with logical explanations for jinn, angels, and prophetic miracles, and he wrote a number of works advocating liberal, logical interpretations of Islamic texts.[116] The response to his claim that Riba mentioned interest charges when lending money to the poor but not to the rich or to borrowers “in trade or in industry” because this financing supported “trade, national welfare and prosperity” was one example. This claim was made in his tafsir (exegesis) of the Quran. Sir Syed claims that although many jurists ruled that all interest was riba, this was done “on their own authority and deduction” rather than in accordance with the Quran.

Anglo-Oriental College Muhammadan

He traveled to England on April 1, 1869, with his sons Syed Mahmood and Syed Hamed. On August 6, the British government bestowed upon him the Order of the Star of India.[118] He visited England’s colleges while traveling the country and was moved by the post-renaissance educational atmosphere. In order to provide Indians with a modern education, Sir Syed returned to India the next year with the intention of constructing a school modeled after Cambridge and Oxford.[119] The Khwastgaran-i-Taraqqi-i-Talim-i-Musalman (Committee for the Better Diffusion and Advancement of Learning among Muhammadans) was founded on December 26, 1870, after he returned.It changed its name to a Fund Committee for the founding of a school by 1872.[120] In an article published sometime in 1872 and reprinted in the Aligarh Institute Gazette on April 5, 1911, Sir Syed outlined his idea for the institution he intended to create:

Although I might seem like Shaikh Chilli when I talk and fantasize, our goal is to transform this MAO College into a university on par with Cambridge or Oxford. Each College will have a mosque, similar to the churches in Cambridge and Oxford. In addition to a Unani Hakim, the college will have a dispensary manned by a doctor and a compounder. Boys living there will be required to participate in the congregational prayers (namaz) at all five times.Students will be dressed in a red Fez cap, a half-sleeved chugha, and a black alpaca. Words that are offensive and derogatory, which boys often learn and become accustomed to, will not be allowed. The term “liar” itself will be deemed an insult and outlawed. They will either eat on European-style tables or on Arab-style chaukis. Chewing betel and smoking cigarettes or huqqa are absolutely forbidden. It will not be acceptable to use corporal punishment or any other form of discipline that could harm a student’s self-esteem. Shia and Sunni guys will be severely prohibited from discussing their differences in religion in the boarding house or at the college.

In an effort to raise awareness of contemporary issues and encourage reforms in Muslim society, he started publishing the journal Tehzeeb-ul-Akhlaq (Social Reformer) on December 24, 1870.[121] Sir Syed sought to integrate tradition with Western education by advocating for a reinterpretation of Muslim thought. In a number of his publications on Islam, he made the case that since the Qur’an was based on an understanding of reason and natural law, being a good Muslim required an awareness of science.By 1873, plans for building a college at Aligarh had been released by the committee led by Sir Syed. Maulvi Samiullah Khan was chosen to serve as the secretary of the planned school’s subcommittee.] The Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental Collegiate School was eventually founded at Aligarh on May 24, 1875, after committee members traveled the nation to raise money for it. The school was transformed into the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College in 1877, two years later.The following year, he gave up practicing law to focus solely on building the college and enacting religious reform.

The British backed Syed’s groundbreaking work.[123] Despite harsh criticism from traditional religious leaders who were against contemporary influences, Sir Syed’s new school drew a sizable student body, primarily from the Muslim middle classes and gentry.[124][Source self-published?] Nonetheless, MAO College had a sizable Hindu student body and was accessible to all communities. A Hindu was the college’s first graduate.[125] In addition to Western and scientific disciplines, the college’s curriculum included religious instruction and Oriental studies.[115] Sultan Shah Jahan Begum, a well-known Muslim noblewoman, was appointed the first chancellor, and Sir Syed asked Theodore Beck, an Englishman, to be the first college principal.[124] In 1885, the college moved to Allahabad University from its original affiliation with Calcutta University.

Muhammadan Educational Conference

Sir Syed recognized the need for a pan-Indian organization to spread the concepts of his movement after establishing the Anglo-Oriental College. He founded the All India Muhammadan Educational Congress, which has its main office in Aligarh, in support of this goal. Maulvi Samiullah Khan presided over the Congress’s inaugural meeting, which took place at Aligarh in 1886. The organization’s primary goals were to elevate the Anglo-Oriental College to the level of a university and encourage Muslim educational advancement through conferences across India. To prevent confusion with the Indian National Congress, the organization’s name was changed to the All India Muhammadan Educational Conference.

Opposition and criticism

The orthodox Indian Muslims resisted Sir Syed’s Aligarh Movement and his plans to establish schools for Western education. The establishment of Anglo-Oriental College was denounced by Imdad Ali, Kanpur’s deputy collector at the time. In opposition to Tehzeeb-ul-Akhlaq, his opponents founded a number of magazines, including Noor-ul-Afaq, Noor-ul-Anwar, and Taed-ul-Islam, to discourage Muslims from joining the Aligarh Movement. He was denounced as a kafir (out of the fold of Islam) by numerous other orthodox Islamic schools] His beliefs sparked “a real hurricane of protests and outbursts of wrath” among the local clergy “in every town and village” of Muslim India, according to J.M.S. Baljon, who issued fatwas “declaring him to be a kafir” (unbeliever).

Additionally, he was charged with becoming a Christian. In a polemic titled Barakat al Dua, the founder of the Ahmadiyya movement, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, criticized several of his writings. Through his publication, Pan-Islamic ideologue Jamal al-Din al-Afghani attacked him harshly, labeling him a “Naturist.”

Many of his personal acquaintances, including Nawab Muhsin ul Mulk, had serious concerns about his religious beliefs, many of which were elaborated in his Qur’anic commentary. The orthodox followers of Waliullahi reform movements, like Ahl-e Hadith and Deobandis, also looked down on Syed Ahmad Khan’s unorthodox beliefs, which included his rejection of miracles, denial of angels’ existence, and downplaying the importance of prophethood.

Many of the leaders of Ahl-i Hadith, including Muḥammad Ḥusayn Baṭālvī (d. 1920 C.E./ 1338 A.H.), declared Sir Syed to be an apostate and declared him Takfir (excommunication). They were especially harsh in their condemnation of Ahmad Khan.

In a letter to an acquaintance of his and Sir Syed’s, Maulana Qasim Nanautawi, the founder of Darul Uloom Deoband, stated:

It would be appropriate for me to show him how much I love him because of this. But because of this (or even more than this), I am really upset and sad for him after learning about his troubled (Fāsid) beliefs..

Political thoughts and activities

Since Sir Syed was primarily an educationist and reformer rather than an academic thinker, his political ideology is tied to the conditions of his era, according to Shan Muhammad’s book Sir Syed Ahmad Khan: A Political Biography. His political perspective was influenced by significant events such as the 1857 Rebellion, William Ewart Gladstone’s administration in England (beginning in 1868), and the viceroyalty of Ripon in India.

Sir Syed had a strong religious conviction. Islam and an Islamic perspective were at the core of his political beliefs.

Sir Syed received a nomination to the Legislative Council of the Viceroy in 1878. In order to encourage the construction of additional institutions and schools throughout India, he provided testimony before the Education Commission.In his early political career, Sir Syed advocated for Hindu-Muslim unity and India’s composite culture, seeking to empower all Indians. In the same year, he established the Muhammadan Association to foster political cooperation among Indian Muslims across the nation, and in 1886, he organized the All India Muhammadan Educational Conference in Aligarh, which advanced his vision of modern education and political unity for Muslims. His writings made him the most well-known Muslim politician in 19th-century India, frequently influencing Muslims’ views on a range of national issues.

Reluctance to participate in active politics

Sir Syed dissuaded Muslims from getting involved in politics. For the betterment of the Muslim community, he believed that obtaining a higher level of English education should come before political goals. As a political agitator, he refused to endorse the National Muhammadan Association, a political organization established by Syed Ameer Ali in 1887, and he did not attend the Muhammedan National Conference in Lahore.

He didn’t say anything about the Indian National Congress when it was founded in 1885, but he later started to actively criticize the group and voice his opposition to it.

Sir Syed promoted voicing complaints to the British government through the constitutional mechanisms, such as administrative involvement. He backed Indian political heavyweights Dadabhai Naoroji and Surendranath Banerjee in their attempts to get Indians represented in the civil service and government. To promote and encourage Muslim graduates to join the Indian Civil Service (ICS), he established the Muhammadan Civil Service Fund Association in 1883. He founded the Muhammedan Association in 1883 to represent Muslims’ concerns before the Imperial Legislative Council. In 1887, Lord Dufferin nominated him to serve on the Civil Service Commission. In order to foster political cooperation, he and Raja Shiv Prasad of Benaras founded the United Patriotic Association in Aligarh in 1888.

Unity between Muslims and Hindus

This lovely bride will turn ugly if one of them is gone.[8] Syed Ahmad Khan was exposed to both Muslim and Hindu holidays while growing up in Delhi, a multicultural city.[8] He was good friends with Debendranath Tagore and Swami Vivekan, and he “had a commitment to the country’s composite culture” in addition to collecting Hindu texts.[8] In an effort to foster harmony between Muslims and Hindus in the 19th century, he opposed the slaughter of cows and even prevented a fellow Muslim from offering one as a sacrifice on Eid al-Adha.[8] On January 27, 1884, Sir Syed spoke before a sizable crowd in Gurdaspur and said:

O Hindus and Muslims! Are you from a nation other than India? Aren’t you buried beneath the earth or burned on its ghats if you live on it? Remember that the terms “Hindu” and “Muslim” are merely religious terms; all of the Christians, Muslims, and Hindus who reside in this country are part of the same nation.

Since its first principal, Henry Siddons, was a Christian and one of its benefactors, Mahendra Singh of Patiala, was Sikh, he allowed Indians of all religions to enroll in Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College.Shafey Kidwai notes that Sir Syed promoted “advocacy of the empowerment of all Indians”.

He called Hindus and Muslims ‘two antagonistic races’ in his book Causes of the Indian Revolt, first published in Urdu in 1858, in which he exposed the British mistake of uniting them in a one race, therefore jeopardizing the British position.

Support for Urdu

Sir Syed emerged as an advocate for the Urdu language at the start of the Hindi–Urdu dispute in 1867.He emerged as a prominent Muslim voice against the United Provinces’ (now Uttar Pradesh’s) decision to make Hindi a second official language. Urdu, which was developed as a synthesis of Muslim and Hindu contributions in India, was seen by Sir Syed as the common tongue of the United Provinces.[8] During the Mughal era, Urdu was created and utilized as a subsidiary language to Persian, which was the court’s official language. Sir Syed encouraged the use of Urdu in his own writings since the fall of the Mughal dynasty.

The Scientific Society solely translated Western texts into Urdu under Sir Syed. Urdu was the medium of instruction in the schools Sir Syed founded. According to Sir Syed, the centuries-old Muslim cultural dominance of India was being undermined by the demand for Hindi, which was mostly driven by Hindus. Sir Syed made the contentious statement that “Urdu was the language of gentry and Hindi that of the vulgar” when testifying before the British-appointed education panel.[148] Hindu leaders reacted negatively to his comments and banded together nationwide to call for Hindi’s recognition.

Sir Syed continued to promote Urdu as the language of all Indian Muslims and as a symbol of Muslim ancestry as a result of the Hindi movement’s success.

Sir Syed continued to promote Urdu as the language of all Indian Muslims and as a symbol of Muslim ancestry as a result of the Hindi movement’s success. His political and educational efforts became more and more focused on and completely in support of Muslim interests. Additionally, he aimed to convince the British to grant Urdu widespread official usage and support. In order to preserve Urdu, his colleagues Mohsin-ul-Mulk and Maulvi Abdul Haq founded groups like the Urdu Defence Association and the Anjuman Taraqqi-i-Urdu.[Reference required] Urdu was adopted as the official language of Hyderabad State and as the medium of instruction at Osmania University as a consequence of the efforts of all these colleagues.

The two-nation theory

It is believed that Sir Syed was the first to suggest that Muslims in the subcontinent should have their own country.He described Muslims and Hindus as two countries in a speech he gave in Meerut in 1888, discussing the overall post-colonial condition. He is regarded as the father of two-nation theory and the originator of Muslim nationalism, which led to the partition of India.

It is believed that Sir Syed’s views on Muslim nationalism, which he had previously expressed in speeches, were altered by the conflict between Urdu and Hindi. Sir Syed was concerned about the loss of Muslim political influence because of the community’s backwardness, but he was also against the idea of democratic self-governance, which would give the Hindu majority control of the government.

“In terms of education and riches, our country is currently in a poor situation, but God has given us the light of religion and the Quran is here to guide us, which has ordained our friendship with them. They are now in charge of us because of God. In order to ensure that their control in India remains stable and durable and does not fall into the hands of the Bengalis, we need establish a friendship with them and use that strategy. We do not want to become subjects of the Hindus instead of the “people of the Book…”, hence our country will suffer if we join the Bengali political movement.

Later in life, he stated:Who would be in charge of India if the English population and army left the country, bringing with them all of their magnificent weaponry, artillery, and other belongings?Could two countries, the Mohammedans and the Hindus, share a monarch and maintain their equal power under these conditions? Definitely not. It is imperative that one of them defeats the other. To wish for both to stay equal is to wish for the unthinkable and the unachievable. However, peace cannot exist in the country until one nation has subdued the other and forced it to submit.

Private life

He wed Parsa Begum, also known as Mubarak Begum, in 1836. They had a daughter, Ameena, who passed away at an early age, and two boys, Syed Hamid and Syed Mahmood.

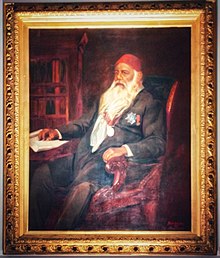

Considered by many to be the guru of Muslim businessmen in the 19th and 20th centuries, Sir Syed Ahmad Khan spent the final 20 years of his life in Aligarh. Sir Syed passed away on March 27, 1898, after battling old age and illness. He was laid to rest in the Aligarh Muslim University campus’s Sir Syed Masjid.

Influence and legacy

In South Asia, Syed Ahmad is largely regarded as a great Muslim visionary and social reformer. Muslim leaders who backed the All India Muslim League were motivated by his progressive ideas and educational approach. In 1886, he established the All India Muhammadan Educational Conference to encourage Muslims in India to pursue Western education, particularly in the areas of science and literature. Along with raising money for Ahmad Khan’s Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College, the meeting inspired Muslim leaders to suggest expanding educational advancement elsewhere, a move known as the Aligarh Movement.He had an impact on a number of political figures, thinkers, and authors, including Muhammad Iqbal, Abul Kalam Azad, Sayyid Mumtaz Ali, Altaf Hussain Hali, Shibli Nomani, Nawab Mohsin-ul-Mulk, Chiragh Ali, and Nazir Ahmad Dehlvi. In turn, this new understanding of Muslim needs helped Muslim elites develop a political consciousness that eventually led Muslims in India to the creation of Pakistan.

His university, which is still regarded as one of India’s most prestigious establishments, was Muslim India’s armory. Muslim political figures Maulana Shaukat Ali, Abdur Rab Nishtar, Maulvi Abdul Haq, and Maulana Mohammad Ali Jouhar are notable Aligarh alums. Among Aligarh’s most well-known alumni are Indian President Dr. Zakir Husain, Liaquat Ali Khan, and Khawaja Nazimuddin, the country’s first two prime ministers. Every year, the university and its alumni commemorate his birth anniversary as Sir Syed Day.

He is the namesake of several educational establishments in India and Pakistan, including Sir Syed College, Taliparamba, Sir Syed University of Engineering and Technology, and Sir Syed CASE Institute of Technolog

Honors

In recognition of his work as Principal Sadr Amin, Syed Ahmad Khan was named a Companion of the Order of the Star of India (CSI) on June 2, 1869. In 1876 and 1887, respectively, the Viceroy named him a fellow of the Universities of Calcutta and Allahabad.

Later, Syed Ahmad received the suffix “Khan Bahadur” and was knighted as a Knight Commander of the Order of the Star of India (KCSI) by the British government in the 1888 New Year’s Honours. for his allegiance to the British monarchy, as seen by his participation in the Imperial Legislative Council and the next year, Edinburgh University awarded him an LL.D. honoris causa.

In Bloomsbury, where he lived from 1869 to 1870, Syed Ahmad Khan was honored in 1997 with an English Heritage blue plaque at 21 Mecklenburgh Square.

In honor of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan’s 200th birthday, the State Bank of Pakistan released a commemorative Rs. 50 coin in 2017.[172]

A commemorative Rs. 75 note showing Syed Ahmed Khan and other founding fathers symbolizing their fight for Pakistan’s independence was released by the State Bank of Pakistan on August 14, 2022, the day of the diamond jubilee celebrations of the country’s independence.