Recent government reports show that crop residue burning, primarily from rice stubble, accounts for only 3.9% of smog in Lahore and 11.1% in Punjab, significantly lower than contributions from the transportation and industrial sectors. The data plainly indicates where the government’s efforts and limited resources should be directed for maximum impact, rather than unfairly scapegoating farmers.

As the intensity and spread of smog in the country increase year after year, farmers’ in-situ burning of rice stubble in October and November to clear their fields for the following (Rabi) crop — wheat, oilseeds, potatoes, vegetables — is dropping in rice-growing areas due to a variety of circumstances.

First, agricultural mechanization is on the rise, aided by provincial government subsidies. Sales data show an increase in the usage of zero-tillage drills, super seeders, and rotavators for wheat sowing. These instruments allow farmers to seed wheat without burning rice stubble.

Second, the sharp increase in electricity and gas prices has forced many enterprises to use biomass as a more cheap energy source, particularly for boiler fuel. To accommodate this requirement, tractor-driven balers collect and condense surplus rice.

Third, the availability of half-feed rice harvesters has increased dramatically during the last two years. These not only reduce harvest losses, but also preserve the complete rice plant after grain threshing (unlike combine harvesters, which slice it up).

Such rice straw is easy to harvest — either manually or with a baler — and has a high economic value due to its numerous use in industrial and rural regions, including crop mulching, animal bedding, and cooking fuel. It is also used as a livestock feed alternative in place of wheat straw, and its demand has recently increased as maize (fall crop) acreage has decreased in numerous districts.

Fourth, rice producers are gradually transitioning from long-duration basmati kinds (130-140 days) to short-duration cultivars such as kissan basmati.

Among all industries contributing to smog, agriculture has the most potential to achieve significant benefits fast and with minimal effort. However, thus far, the government’s strategy has primarily relied on command-and-control tactics — issuing fines and recording first information reports — in a reactive, fire-fighting mode.

These initiatives are essentially chasing shadows, since government offices lack the expertise and resources to efficiently monitor millions of acres of rice fields dispersed across dozens of districts. We must accept that farmers resort to burning agricultural residue due to a lack of balers, labor shortages for manual collection, and increased prices.

Unfortunately, the government has failed to acknowledge that Pakistan, like many other countries, is progressively shifting to a circular bioeconomy.

This can only be achieved by strongly marketing tractor-driven balers through subsidies, particularly for small and medium-sized businesses interested in implementing market-based solutions to reduce smog.

Unfortunately, in the recently formed Roadmap for Smog Mitigation in Lahore (2024-25), the Punjab government concentrates primarily on providing 5,000 subsidised super seeders, completely ignoring balers. Policymakers failed to recognize that a super seeder is only useful for wheat sowing and not for other Rabi crops, particularly large-scale potato planting in Lahore and the neighboring Sahiwal division.

Furthermore, superseeders are most successful in rice fields harvested using a combine harvester. It cannot be used in fields harvested using a half-feed rice harvester without first removing the rice straw, either manually or with.

There is another side to the story: the negative impacts of smog on agriculture, which has gotten insufficient attention from political and policy circles. Agriculture may be the only sector that both contributes to and is affected by smog.

During smoggy months, less sunlight impedes photosynthesis, resulting in restricted plant development, increased vulnerability to insect and pest assault, flower bud loss, and yellowing of foliage. Smog contains a variety of contaminants and chemicals, including ground-level ozone (O3), nitrous oxide, sulfur dioxide, and carbon monoxide, all of which have a severe impact on Rabi crops’ health, yields, and quality. Poor wheat germination due to smog is a problem that directly impacts the country’s greatest staple crop.

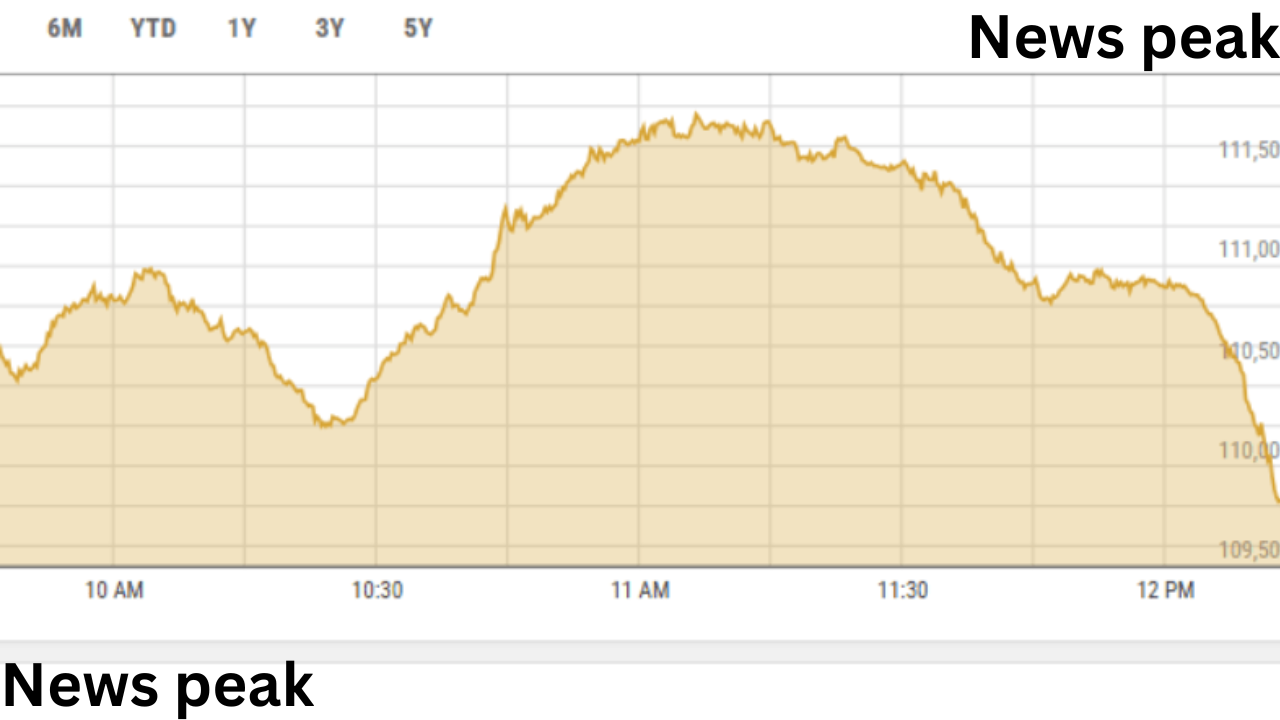

Published in NEWS PEAK, The Business and Finance Weekly, November 18th, 2024